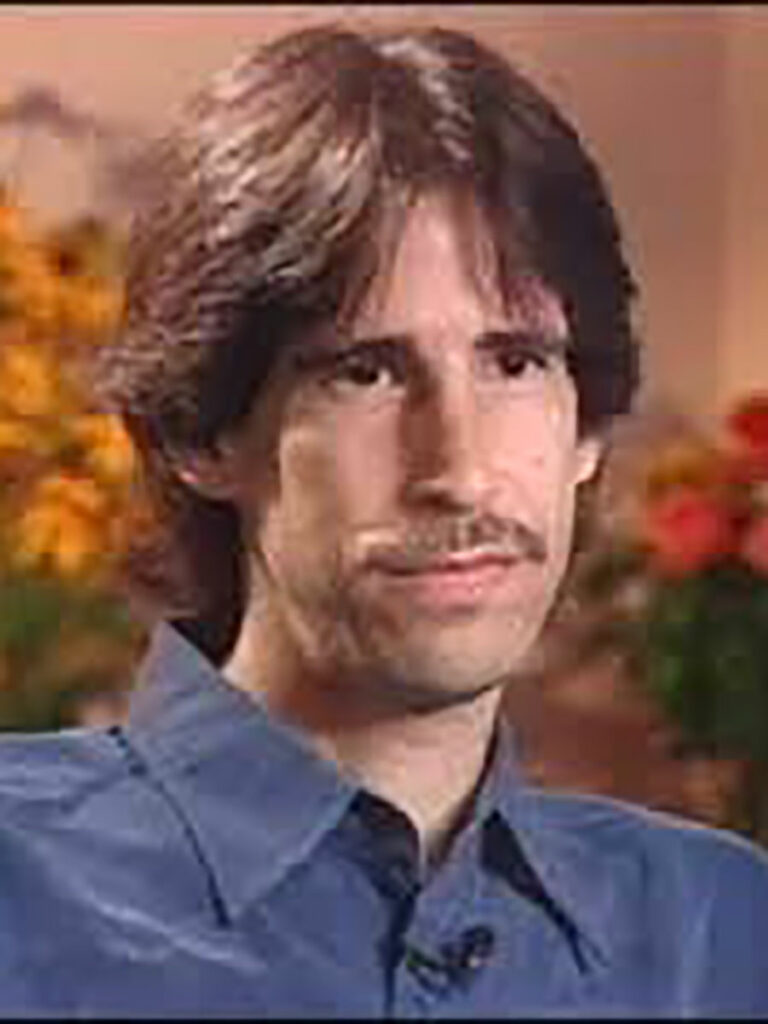

Kyle Unger

Introduction

On Friday, June 22, 1990, nineteen-year-old Kyle Unger attended a rock music festival at a ski resort near his hometown of Roseisle, Manitoba. Brigitte Grenier, then sixteen years old and a high school classmate of Kyle’s, also attended the festival. Between midnight and 1:30 a.m., Brigitte Grenier was observed dancing, kissing and fondling seventeen-year-old Timothy Houlahan. All three-young people had attended the festival separately, with unrelated groups of friends. Neither Kyle nor Brigitte Grenier were friends with Houlahan.

The following day, Brigitte Grenier’s body was found lying in a creek in a heavily wooded area of the concert grounds. She had suffered a terrible beating: she had been bitten, struck several times in the head, and strangled, and long, sharp sticks had been forced into her vagina and anus. The town of Roseisle was distraught and, correspondingly, the pressure on the police to solve the crime was overwhelming.

Evidence against Kyle Unger and Timothy Houlahan

The Night of the Concert

Ms. Grenier and Mr. Houlahan were last seen dancing at approximately 1:30 a.m. They left the dance area together and made their way to a nearby, secluded, wooded part of the ski resort. At about the same time, Kyle went to the washroom; upon his return, he told a friend, John Beckett, that he’d seen Brigitte “going at it with some guy.” Kyle and Mr. Beckett parted ways between 2:00 and 2:30, Kyle having declared that he was going to “look for some tail.”

Beckett estimated that Kyle was out of his sight for as little as 20 minutes, while other witnesses claimed not to have seen Kyle again until 3:30 or 4:00 a.m. There was no disagreement, however, that when Kyle returned to the group he did not have any dirt on his clothing or scratches or bruises to his face. Kyle left the music festival by car between 4:30 and 5:00 a.m.

After entering the wooded area with Ms. Grenier at 1:30 a.m., Mr. Houlahan was next seen between 4:00 and 4:30 a.m. His face and clothes were covered in mud, and he had scratches on his face and blood on his chin. One witness testified that it appeared as though he had received a good beating. Mr. Houlahan claimed that his injuries were the result of a surprise beating by an unknown male, and the reason for his absence was that he had passed out after the beating. Mr. Houlahan continued to party with his friends until the early morning hours when he left the festival. Before leaving, however, he and a friend stopped to set fire to the contents of a barrel near the entrance to the festival area.

The Forensic Evidence

The forensic evidence tendered at the trial against Mr. Houlahan was strong; blood found on his running shoes was consistent with that of the victim, a hair found on Ms. Grenier’s pants was consistent with having originated from Mr. Houlahan’s head, and a pubic hair found on her sock was consistent with having originated from Mr. Houlahan’s pubic hair sample.

The forensic evidence implicating Kyle was a single hair found on Ms. Grenier’s sweatshirt, consistent with the sample of scalp hair he had willingly provided to police. It should be noted, as will be discussed further below, that these samples were taken prior to the advent of DNA technology and their analysis was based on hair microscopy, now regarded as having very limited use in forensic investigations.

The Police Investigation

Kyle and Mr. Houlahan were both interviewed by the RCMP in the days following the murder. The RCMP noted that Mr. Houlahan, whom they visited two days after Ms. Grenier’s body was discovered, had visible markings on his face and hands; however, a statement was not taken from him at that time, as he was a young offender and his parents were not present.

On June 27, the RCMP obtained the first of two formal statements from Mr. Houlahan. In this statement, he admitted to having consensual sex with Ms. Grenier, but claimed that he was thereafter attacked by an unidentified male who left him unconscious. Mr. Houlahan was asked if he’d seen Kyle, whom he would have recognized, at the concert. Mr. Houlahan stated that he had not observed Kyle at the venue, but nevertheless gave police a description of his attacker that led the RCMP to conclude that it was Kyle who had attacked him. Curiously, however, Mr. Houlahan was also asked to describe Kyle, and provided a description very different from his description of the unknown attacker.

In his second statement to the police, Mr. Houlahan directly implicated Kyle in Ms. Grenier’s murder. He gave the police a detailed description of the murder, which was consistent with the forensic and medical evidence. Mr. Houlahan claimed that while Kyle was savagely attacking Ms. Grenier, Kyle insisted that Mr. Houlahan punch her a couple times which he did. Mr. Houlahan also claimed to have assisted Kyle in moving the body and said that he did out of fear for his own safety and under duress.

The Stay of Proceedings

Mr. Houlahan’s case was transferred to adult court, and both Kyle and Mr. Houlahan were charged with first degree murder. Kyle’s preliminary hearing resulted in a stay of proceedings on December 11, 1990.[1] Despite the Crown’s doubts about Kyle’s involvement in Ms. Grenier’s murder, the RCMP held fast to their theory that Kyle was a killer, and set out to find evidence that could bolster their suspicion.

Jailhouse Informant

With only a single hair linking Kyle to the crime scene, the RCMP interviewed upwards of twenty inmates in the hopes of finding someone who would testify that Kyle had confessed to them. In fact, the RCMP found five inmates willing to testify to that effect; however, when the case eventually proceeded to trial, the Crown called only one to give evidence, as the other four had made such bizarre claims that the Crown did not view them as reliable.

The jailhouse informant selected to testify, Jeffery Cohen, claimed that he and Kyle had shared a cell at some point while Kyle was in pre-trial custody. Mr. Cohen swore that immediately before Kyle was released from the Winnipeg Remand Centre following the stay of proceedings, Kyle said to him, “I killed her, and I got away with it.” At trial, however, the defence was able to prove that following the stay, Kyle had been released directly from the courthouse and thus had never returned to the Remand Centre. On the stand, Mr. Cohen admitted he lied, but the Crown nevertheless tried to rehabilitate their jailhouse informant by suggesting that the confession had happened at the Public Safety Building the day before Kyle’s release.

The Mr. Big Operation

The Mr. Big Operation – or, as it is known abroad, the Canadian Technique – is a large-scale undercover operation that involves multiple, and sometimes upwards of 100, undercover officers; costs tens and sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars and takes months or even years to complete. In a nutshell, the undercover officers create a fictitious crime syndicate and lure the target into the “gang,” with the end goal of obtaining a confession to a crime that they are confident the target has committed, usually murder. The RCMP have operated such stings more than 350 times since they began using this technique in the early 1990s. In “Mr. Big” cases where the undercover officers obtain a confession and the case goes to trial, the RCMP report a 95% conviction rate.[2]

Based on the information obtained from Jeffrey Cohen (the jailhouse informant), the RCMP decided to undertake an undercover operation, which commenced on June 13, 1991. On that day, two undercover RCMP officers staged a breakdown of their vehicle outside the hobby farm in rural Manitoba where Kyle lived. In comparison to some of the Mr. Big Sting operations that the RCMP has conducted, the operation targeting Kyle was relatively small. Four officers took part in the sting. The primary undercover officer, Larry Tremblay, befriended Kyle and was tasked with conveying to him that there was an opportunity available to become involved in the criminal organization. On four separate occasions in the first week of the operation, Kyle told his new “friend” that he had been wrongly imprisoned for murder. At no point did P.C. Tremblay request clarification regarding Kyle’s declarations of innocence.

Corporal Larry Forbes was cast in the role of “Mr. Big,” that is, the head of the fictitious criminal organization. Kyle was eager to make a good impression, since he viewed the meeting as a job interview and in addition did not want to embarrass his new friend. Early in their first meeting, on June 22, 1991, Cpl. Forbes said to twenty-year-old Kyle:

“Larry tells me that you whacked somebody. That’s fine with me. That’s, that’s fuckin’ excellent. It’s the kind of thing that, uh, I know that I’m dealing with somebody that’s on my fuckin’ – somebody that I can trust… That’s the kind of person I’m looking for.”

Cpl. Forbes further told Kyle that he did not want to take someone into the organization who had ongoing problems with the police. Kyle, initially hesitatingly and eventually enthusiastically, confessed to the murder. Later he would maintain that he simply acted out the part, to please his new “boss.”

Several additional relevant conversations took place between Kyle’s initial confession and his eventual re-arrest for Brigitte Grenier’s murder, on June 25, 1991. In his conversations with the undercover agents, Kyle contradicted himself with respect to details concerning the murder. Further, police intercepted a conversation between Kyle and John Beckett (the friend with whom he had attended the concert), during which Kyle told Mr. Beckett that he had obtained a trusted position within the criminal organization, where would be making a great deal of money; and that he had obtained this position because of the reputation he had gained because of being charged with murder.

On February 28, 1992, both Kyle and Mr. Houlahan were convicted of first degree murder. Both young men appealed their convictions. On July 7, 1993, the Manitoba Court of Appeal upheld Kyle’s conviction, although it allowed Mr. Houlahan’s appeal and ordered a new trial for him. However, Mr. Houlahan committed suicide before he could be retried. On December 2, 1993, the Supreme Court of Canada denied Kyle’s application for leave to appeal the Court of Appeal’s decision to uphold his conviction.

Innocence Canada and Kyle’s Exoneration

Kyle maintained his innocence, to no avail, throughout the following decade; but finally, the tide turned in April of 2003. DNA results obtained in another Innocence Canada (formerly AIDWYC) client’s case – that of James Driskell – called into question the hair microscopy comparison evidence that had been given at his trial. In an unprecedented and proactive move, the Government of Manitoba, under the leadership of Deputy Attorney General Bruce MacFarlane, set up the Forensic Review Committee, the mandate of which was to ascertain whether there were other cases like James Driskell’s, where DNA typing might shed new light on the validity of previous hair microscopy comparison evidence. Under the Committee’s Terms of Reference, Innocence Canada designated Ian Garber, a lawyer in the private sector of Manitoba, to sit on the Committee.

In the spring of 2004 the Committee decided that Kyle’s conviction fit within their mandate, and arrangements were made for post-conviction mitochondrial DNA typing. The single hair that had been retrieved from Ms. Grenier’s sweatshirt and identified by an RCMP expert as likely belonging to Kyle – that is, the hair which constituted the only forensic evidence linking Kyle to the crime – was scientifically proven not to be his.

On September 13, 2004, Innocence Canada filed an application on Kyle’s behalf with the Minister of Justice, pursuant to section 696.1 of the Criminal Code, for ministerial review of his conviction. The application requested that the Minister exercise his power to quash Kyle’s murder conviction and order a new trial.

On November 4, 2005, Kyle was granted bail pending the Minster’s decision, more than thirteen years after he was convicted. The Federal Minister of Justice ordered a new trial. Four years later, Unger’s name was finally cleared when, on October 23, 2009, Manitoba’s Deputy Attorney General formally withdrew the charges against Kyle and asked that he be officially acquitted.[3] However, there would also be no public inquiry into his wrongful conviction, nor would he be offered compensation.[4] While Kyle’s freedom was no longer in jeopardy, his battle for justice was far from over.

The Causes of Kyle’s Wrongful Conviction

As in most cases that end in a wrongful conviction, there were many factors that contributed to Kyle spending 19 years – 14 of them in jail – during which he was incorrectly believed to have committed a brutal sexual assault and murder. The most significant of these causes are described below.

Jailhouse Informants

Jailhouse informants, sometimes referred to as in-custody informers, are notoriously unreliable sources of testimony and have contributed to many wrongful convictions. According to statistics compiled by the Innocence Project at the Cardozo Law School in New York:[5]

In more than 15% of wrongful conviction cases overturned through DNA testing, an informant testified against the defendant at the original trial. Often, statements from people with incentives to testify – particularly incentives that are not disclosed to the jury – are the central evidence in convicting an innocent person.

The Report of the 1989-90 Los Angeles County Grand Jury Investigation of the Involvement of Jail House Informants in the Criminal Justice System in Los Angeles County (The Grand Jury Report) revealed shocking information about the motivations of jailhouse informants, which cannot be limited to the American experience:[6]

The myriad benefits and favored treatment which are potentially available to informants are compelling incentives for them to offer testimony and a strong motivation to fabricate, when necessary, to provide such testimony. This premise is a basic concept to the understanding of jailhouse informant phenomena. The courts have sometimes lacked adequate factual information to fully realize the potential for untrustworthiness which is inherent in such testimony because of the strong inducements to lie or shape testimony in favor of the prosecution.

Jailhouse informants want some benefit in return for providing testimony. The more sophisticated may attribute their willingness to testify … to other motives such as their repugnance toward the particular crime charged, a family member having been a victim of a similar occurrence, the lack of remorse shown by the defendant, or other explanation to account for their assistance to law enforcement. Nevertheless, in the vast majority of cases it is a benefit, real or perceived, for the informant or some third party that motivates the cooperation.

The benefits can range from added servings of food to the ultimate reward, release from custody. According to an officer at the central jail, inmates who provide information about problems within the jail might be rewarded with an extra phone call, visits, food or access to a movie or television…

As this report chillingly reveals, there are many reasons to be wary of the testimony of a jailhouse informant. Kyle’s case is by no means the only one where an informant’s untrue testimony has contributed to a wrongful conviction.

In Canada, several Commissions of Inquiry – notably the Morin and Sophonow Inquiries – have warned against the use of jailhouse informants.[7] As a result, Crown Prosecutors and the Courts in Canada have changed the way they deal with the evidence of such informants, adopting a much more sceptical and vigilant perspective.[8] That said, there are still some cases where informants are seen as “necessary to the justice system because of their unique position to acquire potential information directly from the accused. Despite obvious reliability problems, they are sometimes relied on to provide persuasive confessions, most notably in the context of high profile murder cases.”[9]

In Kyle’s case, despite the defence counsel’s success in impeaching jailhouse informant Jeffery Cohen, the Crown’s attempt to rehabilitate his testimony – by suggesting an explanation for the impossible story he had told on the stand, other than the obvious (and correct) explanation that he had simply lied – no doubt contributed to the wrongful conviction. As long as jailhouse informants are permitted to testify in court despite their dubious motivations, they will continue to contribute to miscarriages of justice.

Tunnel Vision

Another factor that contributed to Kyle’s wrongful conviction was a common problem known as “tunnel vision” which has been described as “the single minded and overly narrow focus on an investigation or prosecutorial theory” – in this case, the theory that Kyle was guilty of Ms. Grenier’s murder – “so as to unreasonably colour the evaluation of information received and one’s conduct in response to the information.”[10] It is easy for police and prosecutors to fall into tunnel vision, particularly if they are under intense pressure to solve a case. Tunnel vision is therefore a common feature found in many miscarriages of justice.[11] Moreover, “it is a trap that can capture even the best police officer or prosecutor” and thus “must be guarded against vigilantly.”[12]

Mr. Big Stings and False Confessions

The inducements offered in exchange for a confession to a crime by undercover officers posing as organized crime participants can be overwhelming, as they were in Kyle’s case. For Kyle, the seductive promise of money, power and friendship was worth confessing to a crime in which he had played no part. In other Mr. Big operations, violence and fear have also induced the target to confess.

Furthermore, false confessions do not occur exclusively in Mr. Big cases. As noted by the Innocence Project, “in about 25% of DNA exoneration cases, innocent defendants made incriminating statements, delivered outright confessions or pled guilty.”[13] Despite the pervasiveness of this phenomenon, the public – judges and jury members included – have a hard time accepting that someone would confess to a crime that they did not commit. Kyle was not the first, and certainly will not be the last, wrongly convicted person to have made a false confession after succumbing to the pressure of police inducements, coercion, or any number of other factors.

Bad Science

When Kyle was tried in the early 1990s, “hair microscopy” was accepted as “science” in courtrooms across the country. Following James Driskell’s exoneration, an Inquiry was held to determine the causes of his wrongful conviction. Commissioner LeSage recommended in the resulting Report that “microscopic hair comparison evidence should be received with great caution and, when received, jurors should be warned of the inherent frailties of such evidence. ”[14] Following the creation of Manitoba’s Forensic Evidence Review Committee, all Canadian legal jurisdictions reviewed their use of hair comparison evidence.[15] The advent of DNA technology has to some extent rendered hair microscopy obsolete, and so its evidentiary unreliability is less likely to contribute to wrongful convictions in the future.

That being said, as forensic science continues to evolve, it has become clear that many other forensic science techniques are much less reliable than once believed. Shoe print comparison, bite mark analysis, firearm tool mark analysis, and other such techniques that have never been properly tested remain potential causes of wrongful convictions. Furthermore, even reliable, properly validated forensic techniques such as DNA typing, and serology can produce inaccurate results if the samples are contaminated. Finally, the experts tasked with interpreting forensic science evidence for the court may make mistakes that can contribute to miscarriages of justice, as in the many wrongful convictions resulting from the infamously inaccurate testimony of Dr. Charles Smith.[16]

Kyle’s Battle for Justice Continues

As mentioned above, although the Manitoba Crown chose to withdraw the charges against Kyle on October 23, 2009, it was not willing to offer Kyle any financial compensation for the 14 years that he spent in jail. On September 21, 2011, Kyle launched a civil lawsuit naming the RCMP officers and prosecutors who were involved in his wrongful conviction,[17] seeking $14.5 million in damages.[18] Notably, one of the prosecutors in Kyle’s case, George Dangerfield, has also contributed to the wrongful convictions of at least three other Innocence Canada clients: Thomas Sophonow, James Driskell and Frank Ostrowski. Kyle’s civil proceedings are still ongoing. So far both the Attorney General’s Office and the RCMP have refused to take any responsibility for Kyle’s wrongful conviction, instead maintaining that the damage he suffered was “caused or significantly contributed to by … [his] own conduct, which includes, but is not limited to, his repeated admissions of having committed the offence for which he was convicted.”[19] In other words, these officials are implicitly defending the coercive Mr. Big techniques that they employed to induce Kyle to confess to a crime he did not commit. The court date to hear Kyle’s lawsuit has not yet been set.

The Wounds Innocence Canada Cannot Heal

Like many wrongly convicted people, Kyle continues to do battle in the court of public opinion. Ms. Grenier’s death was a tragedy in their small, closely knit community. Like the police who were unwilling to let go of their initial suspicion of Kyle – even in the face of significant evidence of his innocence – many people in Roseisle continue to believe that Kyle killed Ms. Grenier.

Kyle spent his 20’s and early 30’s in prison; and while he has regained his freedom, he will never be able to replace those lost 14 years, but we hope that his future will hold positive life experiences and opportunities that will allow him to grow and achieve his life’s goals.

[1] In Manitoba, the decision to prosecute an offence involves an assessment of whether or not there is a “reasonable likelihood of conviction.” McGoey, Christine, “The “Good” Criminal Law Barrister: A Crown Perspective” The Law Society of Upper Canada: Papers and Videos from Past Colloquia online: The Law Society of Upper Canada http://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCwQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.lsuc.on.ca%2Fmedia%2Fchristine_mcgoey_good_criminal_lawyer_mar0504.pdf&ei=AEsmUqbCLIKU2QXawoGQAw&usg=AFQjCNHRt5wR1fzloX5kPTsrjOBJYXlEOg&bvm=bv.51495398,d.b2I.

[2] Keenan, Kouri T. & Joan Brockman, “Mr. Big Exposing Undercover Investigations in Canada” page 23

[3] CBC News. “Kyle Unger acquitted of 1990 killing.” 23 Oct 2009: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/kyle-unger-acquitted-of-1990-killing-1.783996

[4] Bruce MacFarlane. “Wrongful Convictions: Is It Proper for the Crown to Root Around, Looking for Miscarriages of Justice?” 36 Manitoba Law Journal 1 at 20.

[5] http://www.innocenceproject.org/understand/Snitches-Informants.php

[6] Report of the 1989-90 Los Angeles Country Grand Jury, Investigation of the Involvement of Jail House Informants in the Criminal Justice System in Los Angeles County.

[7] See the Report of the Kaufman Commission on Proceedings Involving Guy Paul Morin at http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/about/pubs/morin; The Inquiry Regarding Thomas Sophonow at http://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/sophonow/toc.html.

[8] See, for example, the Ontario Crown Policy Manual section on In-Custody Informers, at http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/crim/cpm/2005/InCustodyInformers.pdf.

[9] FTP Heads of Prosecutions Committee Report of the Working Group on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice: http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/ccr-rc/pmj-pej/p4.html#foot114at 97.

[10] Morin inquiry, Recommendation 74: http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/about/pubs/morin/morin_recom.pdf

[11] See discussion in Truscott (Re), 2007 ONCA 575, 225 C.C.C. (3d) 321.

[12] “4. Tunnel Vision.” FTP Heads of Prosecutions Committee Report of the Working Group on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice: http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/ccr-rc/pmj-pej/p4.html#foot114

[13] https://www.innocenceproject.org/exoneration-statistics-and-databases/

[14] As quoted in the FTP Report on the Prevention of Wrongful Convictions (page 136)

[15] FTP Report on the Prevention of Wrongful Convictions (page xi)

[16] http://www.innocenceproject.org/understand/Unreliable-Limited-Science.php

[17] http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/kyle-unger-sues-for-wrongful-conviction-in-murder-of-manitoba-teen/article4256694/

[18] Bruce MacFarlane. “Wrongful Convictions: Is It Proper for the Crown to Root Around, Looking for Miscarriages of Justice?” 36 Manitoba Law Journal 1 at 20.

[19] CBC News. Feds deny liability in Kyle Unger wrongful conviction. Aug 27, 201: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/feds-deny-liability-in-kyle-unger-wrongful-conviction-1.1339338.